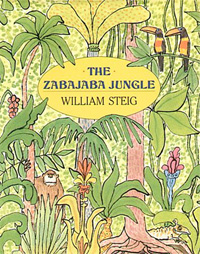

I first began working with William Steig in 1987, the summer before one of his less commercially-successful picture books, The Zabajaba Jungle, was published. “Working with” is a lofty way of describing what I was doing: I was fresh out of college and had just been hired as an editorial assistant at FSG. One of my first tasks on my way to earning my whopping $11,500 annual salary was to pack up and send Bill a box containing his ten contract copies of the book.

After poring over Zabajaba‘s lush 32 pages, I was a Steig convert. The quirky, funny story was a hoot; a few surreal touches added a certain special something; and I admired how it introduced kids (and me) to the word cloaca. Also, it starred a plucky boy hero named Leonard, hacking his way through the wilds to rescue his parents from under a glass jar—what’s not to love about that?

Reviewers weren’t as wild about it as I was, however. This was puzzling to a publishing newbie like me. School Library Journal, for instance, complained that the story lacked the “cohesiveness” of some other Steig picture books, and that the character wasn’t as “sympathetic” as some other Steig heroes. Most reviewers made similar noises. Nothing too harsh, just respectful synopses, with kudos for this bit and knocks for that one. To me it seemed that with all their mixed commentary the reviewers were off their rockers, in part because I still hadn’t learned the hard editorial lesson that just because you love a book doesn’t mean the rest of the world will.

Rereading some of the reviews now, I see that the critics were more right about the book than I was. The Zabajaba Jungle just wasn’t as winning an effort for Bill as I thought it was. It was good stuff but not great stuff. The reviewers knew much more about watching him than I did. They knew more about what he’d done before. They knew he’d already set the bar incredibly high on previous efforts (Sylvester! Brave Irene! Dominic! Doctor De Soto!) and that even a superstar like Bill couldn’t succeed in besting himself each and every time. But they also knew that sooner or later he would really uncork one and soar to an even higher mark. So they were watching his every move attentively.

As it happened, one the many great leaps of Bill’s children’s book career came with the very next book, Shrek! It was published in the fall of 1990, which meant that final art was delivered in the spring of the previous year. So Bill would have been hard at work on the story and sketches in 1988, my second year on the job.

He ventured in to our Union Square office from Connecticut now and again—always dressed natty yet casual, looking ready for a fancy lunch with his editor at Il Cantinori and then to take care of some leaf raking when he got back home. He always had time to chat with me whenever he arrived—cheerfully warning me about the dangers of spending my days working under florescent lights, which he believed were responsible for any number of health issues.

Danger be damned—I carried on working under those harmful rays. (Without a window I had no choice.) And frankly my efforts were invaluable in crafting the dummy. But only on the most uncreative side. I personally was doing all the photocopying and retyping and Scotch-taping and Fed-Ex sending. I was the one taking dictation (!) and typing up editorial notes and cover letters on my ancient IBM as Bill and his editor, Michael di Capua, went back and forth to hone the text and sketches into perfect shape. I may have been consulted on a word choice or two. I definitely ventured out a few times into natural light to carry the layouts back and forth between the designer’s apartment and our offices.

In spite of my limited involvement, I was right there on the edge of things and I knew I was now watching something great unfold. By comparison, for all its rich, tropical scenes and wild story, The Zabajaba Jungle seemed to pale. Something greater, even in the roughest sketches and earliest drafts, was already bursting through the pages of Shrek! I could see that Bill was unleashing an effort for the record books. His Shrek for all his ogre-ness could not be more sympathetic; his story could not be more cohesive. From first line to last, it’s a rocketing ride, full of impish fun, puns, picture-book smarts, and kid-friendly details and developments.

Shrek is utterly unique and we all wish we were more like him, able to make our way from the nest to love and marriage with such zest and aplomb, enjoying the challenge of any and every obstacle, always triumphant.

Of course I could never have known that one day millions of people around the world would know and love this green guy as much as I do. But his success was never surprising to me. And I just consider myself lucky enough to have been there to see the big jump firsthand.

Wesley Adams is an editor at Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.